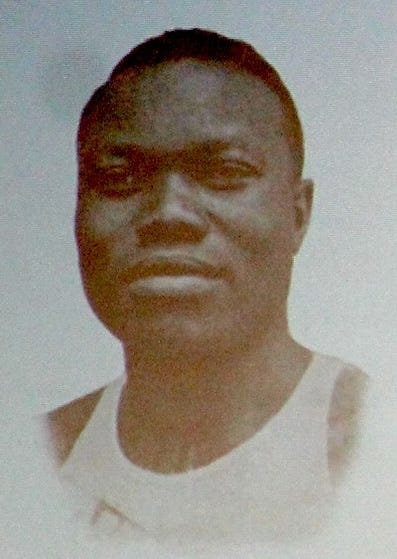

Solomon Butler: ‘The greatest athlete no one has ever heard of’

Former Hutchinson High School standout deserves, attention, recognition

Thanks to the efforts of Steve Miller, former Hutchinson High School football coach from 1976-1984, and author David K. Sebben, former Salthawk great Solomon “Sol” Butler is getting his long overdue recognition for his on-the-field and off-the-field endeavors.

Miller, who is retired from coaching and living in Wichita, wrote a book called “Huddle Up Hutch!: A History of Salthawk Football 1902-2016.” The book features a section on “The Great Solomon ‘Sol' Butler.”

Miller introduced author and teacher David K. Sebben, from Rock Island, Ill., who wrote a book called “Nothing Great is Easily Won: The Solomon Butler Story.” Sebben also attended Rock Island High School.

Sebben gave a PowerPoint presentation to members of the Salthawk football team Wednesday morning in the Hutchinson weight room called “Solomon Butler: “The Greatest Athlete You’ve Never Heard Of.”

“He was a phenomenal person and a phenomenal athlete,” said Sebben.

Sebben said newspapers of the time gave Butler several nicknames, which he accepted: The Black Knight, Smoke, The Black Ghost, The Kansas Whirlwind.

“He was very humble,” Sebben said. “He never bragged about himself.”

“Sol Butler was a great human being,” Miller said. “I was fascinated by Sol Butler. We wanted to revive the memory of Sol Butler. He had a very successful life.”

Solomon “Sol” Butler was born in Kingfisher, Okla., on March 3, 1895, to Benjamin and Mary Butler. His father was born a slave and fought for the Northern Army in the Civil War.

The Butler family moved from Kingfisher because of racial issues to Wichita (where they dealt with similar issues). Then the family moved to Hutchinson in 1909.

Solomon “Sol” Butler was a phenomenal multi-sport athlete in the 1910s and 1920s.

Butler excelled at Hutchinson High School, where the Salthawks won state championships in 1911, 1912 and 1913.

He made the varsity football team as a freshman in 1911. In three seasons, Butler scored 66 touchdowns. The record was broken by Josh Smith, who scored 87 TDs from 2006-2009.

During his sophomore year at HHS in 1912, Butler helped lead the Salthawks to a runner-up finish at the state track meet and set records in the 100-yard dash.

In 1913 as a junior at HHS, Butler during a district meet won six first-place finishes, broke five meet records and unofficially broke a world record in the 50-yard dash.

In 1914, Butler and his brother Benjamin followed his high school coach Herbert Roe to Rock Island High School for his senior year to be close to Chicago, which was a hotbed of track competition in the 1910s.

Butler scored 26 touchdowns his senior year at Rock Island, including eight in one game.

During a regional interscholastic track meet held at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., Butler competed against 300 other track stars.

Butler placed in the 60-yard dash, 60-yard hurdles, 440-yard dash and broad jump (long jump). He broke one meet record, tied one world record and won fourth place by himself competing against entire teams.

Butler earned 12 varsity letters in football, basketball, baseball and track and field at Dubuque German University (now Dubuque University) in Dubuque, Iowa.

“Sol Butler played first base for the Dubuque baseball team when it didn’t interfere with track,” Sebben said. “He played quarterback at Dubuque.”

One of his Dubuque teammates was Johnny Armstrong, another former Hutchinson Salthawk.

“Johnny Armstrong and Sol were lifelong friends,” Sebben said.

Butler won the broad jump competition at the Penn Relays twice and also won the 100-yard dash.

Butler was the first African-American athlete to quarterback a team for all four years of college, according to the Arthur Ashe book “Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African-American Athlete.”

Butler entered military service as a soldier in World War I and represented the U.S. in the Inter-Allied Games in Paris. Butler won the broad jump. Butler was knighted by the King of Montenegro, who was a huge sports fan.

The 1916 Olympics was canceled because of World War I, so Butler competed in the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium. On his first attempt in the broad jump, Butler pulled his hamstring. He placed seventh on the attempt and was forced out of the meet.

“A reporter asked Sol Butler what his single biggest regret was,” Sebben said during the PowerPoint presentation. “He said it was not medaling at the Olympics.”

Butler played five seasons for six teams in the early days of the NFL, including the Rock Island Independents, who defeated the George Halas-owned Chicago Bears 3-0.

“Sol was traded to the Hammond Pros in 1923 for $10,000,” Sebben said. “That was a lot of money in those days.”

Butler played quarterback for one season with Jim Thorpe with the Canton Bulldogs. He played one season in Canton with Paul Robeson and Duke Slater.

In 1926, Canton was scheduled to play the all-white New York Giants (owned by Tim Mara) in front of 40,000 fans, but the Giants refused to play until Canton pulled Butler from the game.

There were very few African-American players in the NFL until 1946 and the Washington Redskins (now the Commanders) didn’t sign black players until 1962.

Butler also pitched one game with the Kansas City Monarchs Negro League Baseball Team.

After his playing days were over, Butler served as recreation director at Chicago’s Washington Park. He was the sports editor of Chicago newspapers The Bee and The Defender.

According to Miller’s book, Butler became friends with famous African-American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux, who grew up in Great Bend. Butler also did bit parts in some of Micheaux’s films and in films by other directors.

Butler acted in a few Tarzan films and a few of Mae West's films. He had a brief part in the film “Showboat” in 1936. Robeson, an actor/singer/Civil Rights activist, was the star of that film. Butler also appeared in the film “Black Fury” with Paul Muni.

Butler also was a boxing promoter and re-opened a cafe previously owned by heavyweight champion Jack Johnson.

Butler died on Dec. 1, 1954, at the age of 59, the day after exchanging gunfire with an angry patron at Paddy’s Liquors, a Chicago tavern where he was employed for even years. The patron died from his gunshot wounds 10 days later.

Butler is buried with other family members at Maple Grove Cemetery in Wichita. His father is buried in Hutchinson.

Miller said in an email to me he has developed a friendship with professor and author Brian Hallstoos from Dubuque University, who is writing another book about Butler.

“Sol is well known even today in Dubuque, mainly because of Brian,” Miller said. “Professor Hallstoos is writing a very scholarly book about Solomon Butler, which delves into what was going on socially and culturally with Sol living life surrounded by integration, hate and the social structures in place limiting advancement.

“I think his book is being published by the University of Illinois Press. I’m guessing his book may be on the shelves hopefully before the end of the year.”

“Long story short, all three of us are simply trying to make people aware of Sol Butler. He was once a household name in Hutchinson, but awareness is dying and we are just trying to keep Sol Butler's legacy alive and well documented.”

Miller said another Solomon Butler researcher is Kansas State Rep. Paul Waggoner, who has served as the 104th district (Hutchinson) representative since 2019.

“I think he has had a few phone conversations with David and Brian,” Miller said.